“While the current combination of fiscal & monetary stimuli might not necessarily result in rising inflation, the addition of fiscal stimulus to the monetary stimulus does provide a powerful additional tailwind for rising commodity prices.”

Andy Pfaff (Coherent Capital Management, 2020)

Cost-push or demand-pull?

The rebound in commodity prices from the pandemic-induced lows of 2020 has continued into 2021. Initially fuelled by the resumption of economic activity as lockdown restrictions were eased, the recovery in commodity prices continues to be underpinned by improved global growth prospects as the vaccine rollout gathers momentum – prompting the IMF to revise its 2021 world economic growth forecast to 6,0% in April this year, up from 5.5% in January.

The positive impact of the demand recovery on prices has been amplified by supply disruptions and logistics constraints caused by the pandemic. Commodity producers have been disciplined as the capital markets have insisted post-2008 GFC and have increased dividends and reduced capex. This persistent underinvestment has significantly constrained supply. A further critical catalyst fuelling the current surge in commodity prices is the concern that the unprecedented monetary and fiscal policies adopted during the pandemic will ultimately fuel a resurgence in inflation after four decades of well-contained price pressures.

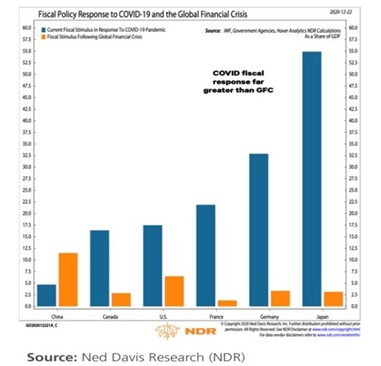

While the GFC of 2008 was met by a huge monetary and fiscal response, in 2013 fears of resurgent inflation prompted a premature tightening in fiscal policy and a weak monetary response (particularly in the eurozone) resulting in a tepid economic recovery and persistently sub-target inflation in both the US and the eurozone. The acknowledgement that the response to a major systemic shock has to be quicker, bigger, and more determined meant that when the Covid pandemic delivered a once-in-a-century shock to the global economy, governments globally implemented unprecedented levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus to stabilise their economies.

Despite these extraordinary measures, market participants generally remain relatively sanguine and continue to forecast a healthy economic recovery accompanied by a modest rise in inflation. The dominant concern of central banks, notably the Federal Reserve, is to raise inflation sufficiently to allow for a normalisation of interest rates – ensuring adequate room for manoeuvre in future.

While inflation has not yet returned – and it remains far from clear that it will return – the probability of an inflationary shock of some kind has undoubtedly been raised providing a further underpinning for the commodity bull market.

Commodity supercycle?

“The world consumes oil but isn’t ready to invest in it. As a result there is a risk of a severe deficit of oil and gas.”

Igor Sechin, CEO Rosneft 2021

Analysts and strategists are similarly grappling with the question of whether resurgent demand and insufficient supply will create a new commodities supercycle – a view espoused by multiple commodity producers and endorsed by the likes of Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan. Commodity supercycles are rare, but long lasting. Since the mid-19th century, there have been just four supercycles – each underscored by major historical events. The most recent supercycle, which started in 2000, was driven by urbanisation, investment, and an ascendant middle class in emerging markets – most notably China – and was ended by the 2008 global financial crisis.

Proponents of a new supercycle argue that commodity prices will be driven by stimulus spending, which places greater emphasis on job creation and environmental sustainability than on inflation control, as well as on spending in China, rising inflation, and a weaker dollar. This macroeconomic backdrop should ultimately prove to be more supportive of real assets like commodities than financial assets.

Commodity bulls also anticipate that the global transition to clean energy will generate a persistent supply gap, reinforcing the supercycle. Significant infrastructure investments as the world reduces its reliance on carbon should drive up demand of several raw materials, including aluminium, copper, silver & zinc. Copper in particular has been identified as a key beneficiary of the push for a green future as it is essential for electric cars, solar panels, wind turbines and 5G infrastructure.

Sceptics argue that while commodity price cycles are common, supercycles are different – requiring a fundamental shift in demand or supply to ensure elevated prices for an extended period. Rather than a new supercycle, these analysts argue that the current commodity boom is merely a cyclical recovery driven by restocking in the US, China, and Europe – with prices boosted by supply disruptions. Furthermore, supercycles typically only occur every 30 to 40 years, while the last one ended just over a decade ago.

The politics of preferences and constraints

“Politicians function in a world bounded by preferences and constraints”

(Marko Papic: Geopolitical Alpha, 2020)

Post-2008 policies have been characterised by monetary stimulus. This has resulted in asset price inflation and has benefitted the asset-owning community.

Post-Covid, the global median voter has shifted markedly to the left, imposing economic policy constraints on politicians. So, as much as independent central banks may prefer monetary discipline and financial stability, constrained politicians worldwide have no choice but to implement expansive fiscal policies with their trickle-down benefits to the wage-earner rather than the asset-owner. Central banks will therefore stomach higher inflation and steeper yield curves to kick-start the money multiplier to avoid the “Japanification” of their economies. This fiscal stimulus is likely to continue to increase – something difficult for investors rooted in the Washington-consensus era to contemplate.

This fiscal stimulus will inevitably affect the commodity demand/supply balance, increasing demand for energy and metals in particular. As commodity prices are determined by current demand and supply, rather than the present value of future cash flows method of valuing financial assets, this increased demand will result in rising commodity prices until the supply side is able respond with increased supply, albeit in new areas befitting the technological progress accelerated by the Covid-lockdown remote-working economy (e.g. clean energy).

While this combination of fiscal & monetary stimuli might not necessarily result in rising inflation, the addition of fiscal stimulus to the monetary stimulus does provide a powerful additional tailwind for rising commodity prices.

Figure 1 fiscal stimuli post-GFC vs. post-Covid

Author: Andy Pfaff

Download a PDF version of this article.